Fan Micro Car DIY STEM Kit

$9.99$5.55

Posted on: Jul 11, 2003

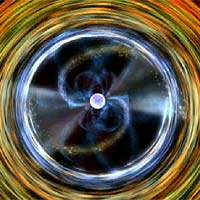

A pulsar’s spin rate would be increasing due to the influx of material from its companion star.

Image courtesy NASA.

Gravitational radiation, ripples in the fabric of space predicted by Albert Einstein, may serve as a cosmic traffic enforcer, protecting reckless pulsars from spinning too fast and blowing apart, according to a report published in the July 3 issue of Nature.

Pulsars, the fastest spinning stars in the Universe, are the core remains of exploded stars, containing the mass of our Sun compressed into a sphere about 10 miles across. Some pulsars gain speed by pulling in gas from a neighboring star, reaching spin rates of nearly one revolution per millisecond, or almost 20 percent light speed. These "millisecond" pulsars would fly apart if they gained much more speed.

Using NASA's Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer, scientists have found a limit to how fast a pulsar spins and speculate that the cause is gravitational radiation: The faster a pulsar spins, the more gravitational radiation it might release, as its exquisite spherical shape becomes slightly deformed. This may restrain the pulsar's rotation and save it from obliteration.

"Nature has set a speed limit for pulsar spins," said Prof. Deepto Chakrabarty of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, lead author on the journal article. "Just like cars speeding on a highway, the fastest-spinning pulsars could technically go twice as fast, but something stops them before they break apart. It may be gravitational radiation that prevents pulsars from destroying themselves."

Chakrabarty's co-authors are Drs. Edward Morgan, Michael Muno, and Duncan Galloway of MIT; Rudy Wijnands, University of St. Andrews, Scotland; Michiel van der Klis, University of Amsterdam; and Craig Markwardt, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Wijnands also leads a second Nature letter complementing this finding.

Gravitational waves, analogous to waves upon an ocean, are ripples in four-dimensional spacetime. These exotic waves, predicted by Einstein's theory of relativity, are produced by massive objects in motion and have not yet been directly detected.

Created in a star explosion, a pulsar is born spinning, perhaps 30 times per second, and slows down over millions of years. Yet if the dense pulsar, with its strong gravitational potential, is in a binary system, it can pull in material from its companion star. This influx can spin up the pulsar to the millisecond range, rotating hundreds of times per second.

In some pulsars, the accumulating material on the surface occasionally is consumed in a massive thermonuclear explosion, emitting a burst of X-ray light lasting only a few seconds. In this fury lies a brief opportunity to measure the spin of otherwise faint pulsars. Scientists report in Nature that a type of flickering found in these X-ray bursts, called "burst oscillations," serves as a direct measure of the pulsar's spin rate. Studying the burst oscillations from 11 pulsars, they found none spinning faster than 619 times per second.

The Rossi Explorer is capable of detecting pulsars spinning as fast as 4,000 times per second. Pulsar break-up is predicted to occur at 1,000 to 3,000 revolutions per second. Yet scientists have found none that fast. From statistical analysis of 11 pulsars, they concluded that the maximum speed seen in nature must be below 760 revolutions per second.

This observation supports the theory of a feedback mechanism involving gravitational radiation limiting pulsar speeds, proposed by Prof. Lars Bildsten of the University of California, Santa Barbara. As the pulsar picks up speed through accretion, any slight distortion in the star's dense, half-mile-thick crust of crystalline metal will allow the pulsar to radiate gravitational waves. (Envision a spinning, oblong rugby ball in water, which would cause more ripples than a spinning, spherical basketball.) An equilibrium rotation rate is eventually reached where the angular momentum shed by emitting gravitational radiation matches the angular momentum being added to the pulsar by its companion star.

Bildsten said that accreting millisecond pulsars could eventually be studied in greater detail in an entirely new way, through the direct detection of their gravitational radiation. LIGO, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory now in operation in Hanford, Washington, and in Livingston, Louisiana, will eventually be tunable to the frequency at which millisecond pulsars are expected to emit gravitational waves.

"The waves are subtle, altering spacetime and the distance between objects as far apart as the Earth and the Moon by much less than the width of an atom," said Prof. Barry Barish of the California Institute of Technology, the LIGO director. "As such, gravitational radiation has not been directly detected yet. We hope to change that soon."